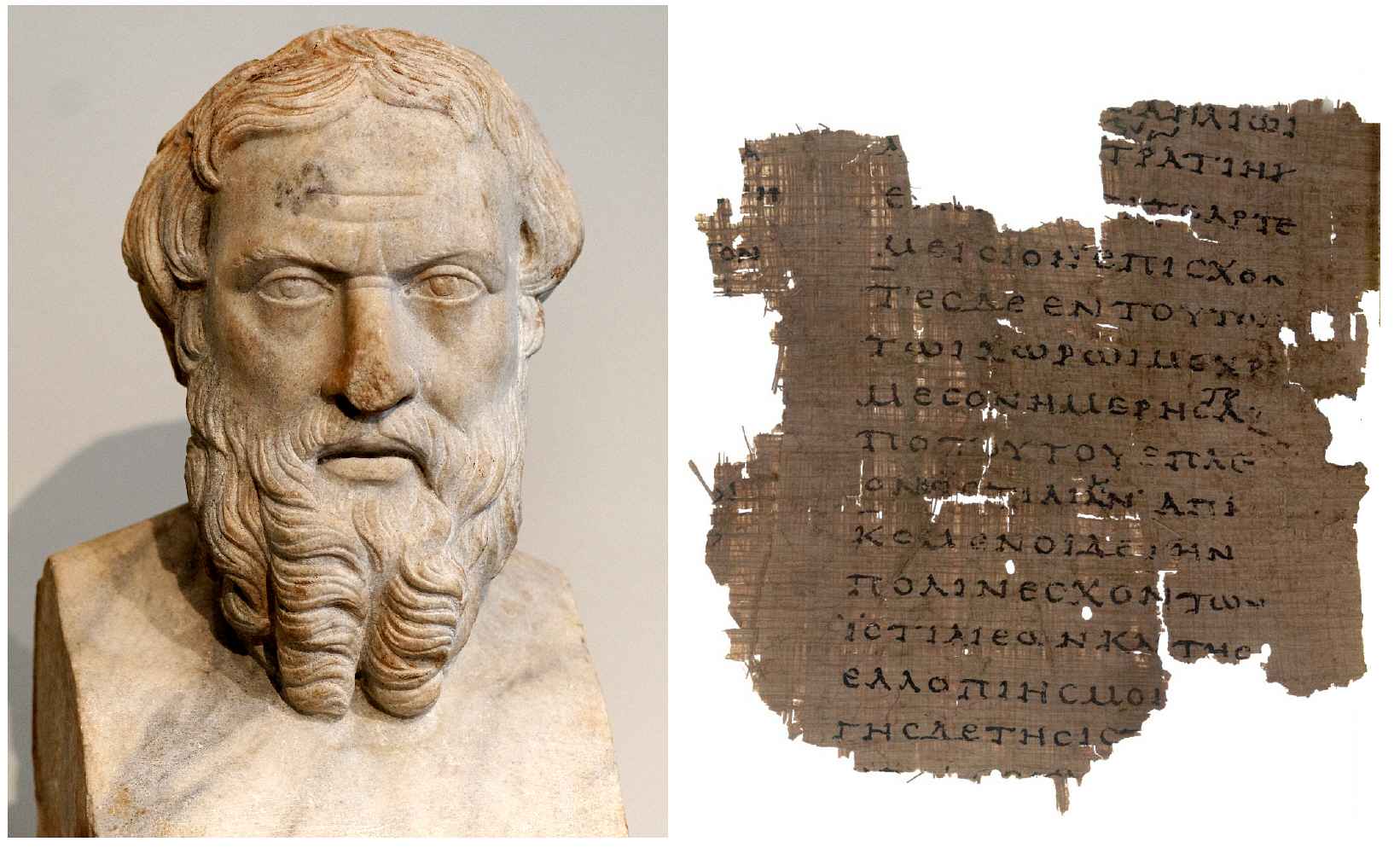

Biography of Herodotus – the ‘Father of History’ !

Herodotus was the first and foremost historian, and is regarded as the ‘father of history’.

He placed historical events in a geographical setting; some of his writings are truly geographical in character.

He not only described geographical phenomena as, for example, the annual flow of the Nile but also attempted to explain them.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

He was also one of the pioneer geographers. He was a strong supporter of the idea that all history must be treated geographically and all geography must he treated historically. His work is an excellent example of historical geography. While describing the surface of the earth, he gave an interesting account of the then existing tribes and their lifestyles. Anthropologists consider him as the foremost enthnographer.

Herodotus was born at Halicarnassus in the 5th century B.C. He stayed at Athens—the main centre of Hellenic culture; afterwards from Athens in 433 B.C., he went to Thurii—a town in South Italy.Herodotus wrote most of his works at Athens before leaving for Thurii, but these were completed at Thurii only.

Herodotus was a great traveller and his contribution to geography is highly remarkable as he wrote after making personal observation during many years of travel. Westward he visited Italy and through the strait of Marmara and Bosphorus (Turkey) reached the Euxine Sea.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Traversing the Euxine he reached the Persian Empire, and stayed at Susa and Babylon. Moreover, he was quite familiar with the coasts of Asia Minor, as also with the island of the Aegean, the mainland of Greece, Byzantium, and the neighbouring shores of Thrace. He made voyage to Tyre. The land of Colchis was also visited by him. Towards the south he travelled several times to Egypt and ascended most probably up to the Elephantine cataract (present Aswan). In Libya, he reached Cyrene to see the statue there of which he gave an eyewitness description.

Herodotus’ views about the shape of the earth were not in conformity with those of Hecataeus that the earth, as a circular plane, is surrounded by an ocean stream. He accepted the Homeric view of the earth as a flat disc over which the sun travelled in an arc from east to west.

He belonged to the Pythagorean School of Philosophy and thus tried to establish a symmetrical correspondence in the distribution of land, and in the source, direction and course of the Ister (Danube) and Nile rivers. His knowledge of the source and upper course of the Nile was highly erroneous. He was convinced that when there were inhabitants on the back of the northerly winds (Bores), there should also be tribes on the back of the southern winds.

The land, according to him, is divided into two equal parts, one lying to the north of the line passing through Hellespont, the Euxine, on the Caucasus Mountains and the Caspian Sea. Thus, Europe was taken to be equivalent to Asia and Libya (Africa) combined. About the Nile river, he stated that it flowed in a direction from west to east, dividing Libya through the middle into two parts.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The source of the Nile was in the west of Libya, almost the same distance as that of Ister in Cells near the city of Pyrene. Ister, according to him, flowed through the whole of Europe and before discharging its water into the Euxine Sea, adopted a north-south course like the Nile River. Egypt, according to him, lay almost exactly opposite the mountain portion of Cilicia (Turkey) and the peninsula of Sinope. Cilicia (Turkey) lay opposite to the place where the Ister fell into the Black Sea.

It was a crude manner of drawing a meridian from the mouth of Nile to that of Ister (Fig. 1.3). The primitive cosmic beliefs of Herodotus were highly erroneous. He believed that the sun was driven southward out of its regular course by the winds at the approach of winter. In spite of all such unscientific beliefs, he was the first scholar who tried to draw a meridian on the world map. The meridian was drawn from Egypt to Cilicia (south coast of Turkey), peninsula of Sinope and the mouth of Ister (Danube). In his opinion, all these fell in a north-south line, which could be taken as the meridian.

So far as the spread of continents is concerned, Herodotus did not have a clear idea and could not fix the northern limit of Europe. He also did not have any idea of the existence of the north-eastern seas. On the southern side, he felt that the ocean sprawled continuously from the coast of India to that of Spain (Fig. 1.3).

In support of his conviction, he asserted that Scylax had sailed from the mouth of Indus to the Red Sea, and Necho voyaged from Egypt to explore the coast of Africa and succeeded in reaching the Pillars of Hercules by the southern side. He was familiar with the Arabian Sea, the Indian Ocean (Arythraean) and the Atlantic Ocean and believed in only two inland seas, one stretching northward and the second eastward from the Indian Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean respectively, i.e., Red Sea (Arabian Gulf) and the Mediterranean Sea. He was ignorant of the Persian Gulf (Fig. 1.3).

So far as the Euxine (Black Sea) is concerned, he had himself navigated in it. In fact, the Greek traders were quite active in the Black Sea. His knowledge of the Euxine and the land and tribes lying to the north of it was more correct as compared to his predecessors. He wrote that the Euxine, “the most wonderful of all seas”, is 1,100 stadia (110 miles) in length and at the widest portion it is 1,300 stadia (130 miles).

His idea of the size and dimensions of Palus-Maeotis, “the mother of the Euxine” (Sea of Azov), was, however, erroneous. In reality, the Sea of Azov (Palus-Maeotis) is not much more than one-twelfth of the size of Black Sea (Euxine). The supporters of Herodotus feel that the Sea of Azov is a shallow one and might have shrunk in the last two and a half thousand years or so. According to geologists, the Don River is pushing its delta into the Sea of Azov. Even making allowance for the silting of the Palus-Maeotis, its sprawl is greatly exaggerated. Herodotus showed the Palus-Maeotis in a north-south direction drawing a boundary between Europe and Scythia which is also not correct.

Herodotus is the first geographer who regarded the Caspian as an inland sea, whereas Hecataeus and his contemporaries as well as all the geographers of Alexandrian era considered it as an arm of the Northern Ocean (Fig. 1.3). In respect of the Caspian, it is remarkable that Herodotus was in advance of almost all his successors.

Herodotus was well aware of some of the physical processes that transform the surface of the earth. He insisted that the Nile Valley, especially its delta, has been built by silt and mud brought down by the river from Ethiopia. This mud is black in colour which can be ploughed easily. Furthermore, he supports the hypothesis that the Nile mud deposited into the Mediterranean Sea had built the delta. He reconstructed the ancient shore line and showed that many sea ports were now far inland. He explained the process of delta making and stressed the point that the delta of Meander River (West Turkey) was also the result of river deposition. Similarly, he tried to establish a relationship between temperature and the movement of winds.

Herodotus was also the first scholar who divided the world land- mass into three continents, namely, Europe, Asia and Libya (Africa). The size of Europe has, however, been taken as equivalent to Asia and Libya (Africa) combined. It is surprising that he took the western frontier of Egypt as the boundary between Asia and Libya. Asia and Europe were divided by the Strait of Bosforus, the Tanais (Don) river, the Caspian Sea and Araxes (Amu). It would be worthwhile to examine in brief the knowledge which he possessed about the physical features and tribes of these three continents.

Of the greater parts of Europe his knowledge was scanty. He described Ister (Danube) as the greatest river of the world and the Carpis (Carpathian Mountains) and Alpis (Alps mountains) as its two major tributaries. The description of Central and Western Europe was scanty. He plotted the Ombri and Eneti nations in the northern parts of Italy but was not familiar with Great Alps which separate these from the tribes of the north.

Scythia, the land to the west of Palus-Maeotis and to the north of the Euxine, was best known to him as this land was occupied by the Greek traders and he himself also travelled that part of the world. He probably stayed for some time in the land lying between Olbia and Borysthenes (Dniester river) (Fig. 1.3).

The Borysthenes is considered by Herodotus as the largest river of Scythia after the Danube. Its plain was regarded as the most productive in the world excepting the Nile Valley. The inhabitants of this region were called ‘Olbia’ (the prosperous). Tanais (Don) is another river mentioned by Herodotus. Thus, the knowledge of Herodotus about the Scythian rivers was appreciably good. But, as he recedes from the coast, his information becomes vague and untrustworthy.

The Scythian people as conceived by Herodotus were divided into several tribes. Characterized by some difference in their modes of life and habits, these tribes were spread in different geographical locations. He held that the tribes dependent on agriculture dwelt in the valley of Borysthenes; moving eastward the area was occupied by nomads and along the coast of Palus-Maeotis lived the royal tribe. Among the other tribes Agysthrsi, Neuri, Androphagi, Melanchaeni, Geloni, Budini and Sauromatae were prominent. All these tribes had their own separate rulers, and were, in the opinion of Herodotus, distinct from the Scythians. Agythrsi people were considered the most refined among them; they wore gold ornaments.

The Neuris resembled Scythians in manners but were said to have the peculiar power of transforming themselves for a few days every year into wolves. Beyond the Neuris were the Androphagis (Cannibals). Their manners in all respects were most rude and savage and they spoke a language different from Scythians. To the east of these was the homeland Melanchalaenis (Black Cloaks) about whom much information is not given.

The Budinis have been considered as blue-eyed, with red hair, a well-built powerful tribe. They were nomads, like their neighbours on both sides, but their land was thickly forested. The Geloni were settled farmers. According to Herodotus, their origin was from Greece, having migrated to Scythia. The Argippaens were the last people towards the north. They were the people who lived to the east of Urals. The people living to the east of the Caspian Sea were Issedones and Massagataes.

Herodotus’ knowledge of Asia was confined mainly to the Persian Empire which sprawled over the whole of Western Asia (with the exception of the Arabian Peninsula) from the Erythraean Sea to the Caucasus and the Caspian, and from the coast of the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea to the Indus. Beyond these regions his knowledge was vague.

The Persian Empire for the purpose of administration and revenue collection was divided into twenty satrapies (provinces). He was acquainted with these satrapies and their principal tribes. From the Erythraean Sea (Arabian Sea) towards the Caspian Sea he placed four major tribes, i.e., Persians, Medes, Saspirians and Colchians.

His knowledge about the Peninsula of Anatolia (Turkey) and Asia Minor which was surrounded by the Greek colonies was very inaccurate. He was not aware of any of the great mountain chains of Asia like Tarus, Elburz, Zagros, Hindu-Kush and the Himalayas. Nevertheless, he was conversant with the courses of Tigris and Euphrates and their sources in the highlands of Armenia.

Herodotus gave a good account of the Royal Road, joining the city of Sardis to Susa (Fig. 1.3). This road, according to him, was marked by royal stations at regular intervals. At each station, there were ‘carvan-sarais’ (rest-houses). This road was about 13,500 stadia (1,350 miles) which is very close to the actual distance between Sardis and Susa.

Herodotus alluded to the Erythraean Sea as situated to the south of Asia, extending from the Arabian Gulf (Red Sea) to the mouth of the Indus. The account of India and its inhabitants by Herodotus is interesting and instructive. He was not familiar with the fertile Gangetic plain and considered the Indus as flowing in a west-east direction. To the east of the Indus there was no tribe and the area as described by Herodotus was a big sandy desert. He was not sure of the eastern limit of Asia and the existence of a sea to its east.

He had, in his opinion, the only river, except the Nile, in which they were found. Curiously enough, he has nowhere referred to the elephants of India. Albeit he knew that the Indians used or grew cotton which resembled wool. They also grew a large kind of reed (bamboo), used for making bows. Caspatyrus was the only city known to him.

Herodotus also possessed enormous information about the continent of Africa. His knowledge of the southern coast of the Mediterranean Sea was as accurate as that of its northern coast. In fact, he himself visited Cyrene (Aswan), which was at that time an important centre of Greek life and culture. Up to the point of Carthage, his knowledge was pretty correct. With regard to the interior of the continent his knowledge was confined to the course of the Nile River. He himself ascended up to the Elephantine just below the First Cataract.

The Cataract he described that owing to the rising of the ground “it is necessary to attach a rope to the boat on each side, as men harness an ox, and so proceed on the journey”. The next important station along the bank of the Nile was Maroes—the capital of Aethiopians (Ethiopia). Meroes city was to the north of Khartoum. The only people of whom he had heard as situated beyond Meroes were a race called Asmach (or deserters).

These people occupied the territory to the south of Khartoum between the two branches of the Nile, i.e., the Blue and the White Nile. According to Egyptians, they had left Egypt during the period of Psammitichus owing to his brutality and hard service conditions.

The Macrobian Ethiopians were regarded by Herodotus as the remotest dwellers, occupying the southern most parts of Africa. They, he presumed, were the tallest and the most handsome race in the world and lived for an average of 120 years. Gold was so abundant in their country that it was used even for the chains and fetters of prisoners. They enclosed the dead in pillars of transparent crystal instead of coffins, their food consisted solely of meat and milk and this was the main cause of their high longevity.These people were none but the inhabitants of Somalia, opposite the Red Sea.

With the western coast of Africa, Herodotus was less acquainted. The northern coast of Africa was divided into the eastern and western portions. The eastern part was sandy and its people were nomads. The land was barren; the city of Syrene was situated in this tract. The western tract was characterized by hills, fertile valleys and dense forests. The western coast of the coastal Africa was occupied by primitive tribes with whom the Carthagians practise ‘dumb commerce’. Still there are certain primitive tribes in the tropical world who practise this type of barter. The dumb commerce has been described by Herodotus in the following words:

There is a country in Libya, and a nation, beyond the Pillars of Hersules, which the Carthagians are wont to visit, where they no sooner arrive but forthwith they unload their wares, and, having disposed them after an orderly fashion along the beach, leave them, and returning aboard their ships, raise a great smoke. The natives, when they see the smoke, come down to the shore, and lying out to view such gold as they think the worth of the wares, withdraw to a distance. The Carthagians upon this come ashore and look. If they think the gold enough, they take it and go their way, but if does not seem to them sufficient, they go aboard ship once more, and wait patiently.

Then the other approach and add to their gold, till the Carthagians are content. Neither party deals unfairly by the other: for they themselves never touch the gold till it comes up to the worth of their goods, nor do the natives every carry off the goods till the gold is taken away.

No indication is furnished by Herodotus of the locality where this dumb commerce was carried on: but the fact of gold being the object of the trade leads to the inference that it was at a considerable distance towards the south, as there is very little gold found to the north of Sahara.

Herodotus divided the interior parts of Africa into three latitudinal zones. The first zone is the Mediterranean coast from Atlas Mountains to the delta of Nile. It is partly occupied by nomads and partly by cultivators. The second zone to the south of it is the area of ‘wild beasts’. By the Arabs this was called the ‘land of dates’.

The third zone which lies further south is the true Sahara desert. Herodotus has mentioned that in the desert of Sahara there are five oases, namely, Ammonium (Siwah), Augila, Garamantes, Atarantes and Atlantes (Fig. 1.3). They lie at a distance of ten-day journey from one another.