Read this article to learn about the administration of the East India Company and Crown during the British rule in India!

Evolution of Central and Provincial Structure Under the East India Company:

Regulating Act of 1773:

i. The Act provided that the Court of Director hitherto elected every year, was henceforth to be elected for four years. The number of Directors was fixed at 24, one-fourth retiring every year.

ii. In Bengal a collegiate government was created consisting of a Governor – General having a casting vote when there was an equal division of opinion. The first Governor-general (Warren Hastings) and councillors (Philip Francis, Clavering, Monson and Barwell) were named in the Act.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The Governor-General-in-Council were vested with the civil and military government of the Presidency of Fort William in Bengal.

iii. The Act empowered the Crown to establish by charter a Supreme Court of Judicature, consisting of a Chief Justice and three puisine judges which was given both original and appellate jurisdiction. All British subjects in Bengal, European and Indian, could seek redress in the Supreme Court. It was constituted in 1774 with Sir Elijah Impey as Chief Justice.

Pitt’s India Act, 1784:

i. The Act of 1784 introduced changes mainly in the Company’s Home Government in London. While the patronage of the company was left untouched, all civil, military and revenue affairs were to be controlled by the Board of Control consisting of 6 members.

ii. In India, the chief government was placed in the hands of Governor-General and council of three.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

iii. The Presidencies of Madras and Bombay were subordinated to the Governor – General and Council of Bengal in all matters.

iv. Only covenanted servants were in future to be appointed members of the Council of the Governor-General.

The Charter Act of 1793:

i. In 1793, the Company’s commercial privileges were extended for another twenty years.

ii. The power which had been specially given to Cornwallis on his appointment to over-ride his Council was extended to all future Governor – Generals and Governors.

The Charter Act of 1813:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

i. By this Act, the company was deprived of its monopoly of trade with India but it still enjoyed its monopoly of trade with China and the trade in tea.

ii. The Act continued to the Company for a further period of twenty years the possession of the territories and revenues.

iii. It contained a clause providing for a sum of one lakh of rupees annually for the spread of education.

The Charter Act of 1833:

i. It completed the introduction of free trade in India by abolishing the company’s monopoly of trade in tea and trade with China.

ii. All restrictions on European immigration into India and acquisition by them of land and property in India were removed.

iii. The Act centralised the administration of India. The Governor-General of Bengal became the Governor-General of India (William Bentinck was the first Governor-General of India).

iv. The Act also brought about legislative centralisation. The Governments of Madras and Bombay were drastically deprived of their powers of legislation.

v. The Act enlarged the Executive Council of the Governor General by the addition, of the fourth member (Law member) for legislative purposes. Macaulay was the first law member.

vi. Section 87 provided that ‘no Indian or natural – born subject of the Crown resident in India should be by reason only of his religion, place of birth, descent, colour, be disqualified for any place of office or employment under the company.

The Charter Act of 1853:

i. The Act renewed the powers of the company and allowed it to retain possession of Indian territories ‘in trust for her majesty’, not for any specified period but only “until Parliament should otherwise provide.”

ii. The number of the members of the Court of Directors was reduced from 24 to 18 out of 6 were to nominated by the crown.

iii. The Law Member was made a full member of the Governor-General’s Executive council and this Council while sitting in its legislative capacity was enlarged by the addition of six members.

Paramountcy:

British rule in India started paramountacy in all fields of governance. Though prior rulers also made several organisations to run their Government but those were not as organized as were during British rule. British practices in the process of paramountacy have been described below:-

Civil Service:

The British Raj and the Indian colonial civil service were ‘symbiotically’ related to each other. If the principal pillar on which the whole of the superstructure of the Raj rested was the Indian civil service, then also true was the fact that it, on its part, provided the irresponsible civil servants on ‘playground’ and ‘rules’ of the game with adequate room for both ruthless repression as well as skillful adjustments.

First Charter from Queen:

The British ‘intercourse’ with India started from 1600, when the East India Company obtained a charter from Queen Elizabeth I granting it “monopoly at the trade with the East”.

First Step of Administrative Club:

In one of the ships of third expedition of the Company in 1607-8, arrived Sir William Hawkins, the first civil servant, not in the strict sense of the term, but only in the sense of his distinctiveness from a military servant, more appropriate for commercial ventures than for an administrative ‘club’. From this date till 1750’s, most of the so-called civil servants were alien free booters interests only in making their fortunes in the shortest possible time-frame.

They carried on inland trade in salt, and tobacco, used and misused the dastaks, received nazarana, rishwats and dasturs and finally, returned to their home. ‘Acceptance of presents was customary in India and there was no person in Company service who had not done so’, agreed Clive.

This ‘shaking of the pagoda trace’ transformed ‘the granary of India’ (Bengal) into ‘a confused heap as wild as chaos itself. Clearly, the ‘civil servants’ of this generation were interested more in rapid swelling of their money bag than in the administrative responsibility.

Practices of Warren Hastings:

The arrival of Warren Hastings in Bengal as Governor of the presidency of Fort William in 1772 proved to be a turning point in this direction. The same year, the Company was ordered by the Court of Directors to stand forth as ‘Diwan’ which meant the termination of system of ‘dual government’ and imposition of an administrative task upon the commercial men and thus the foundation of the civil service was formally laid.

Accordingly, Englishmen were to be appointed as Collectors in district under the overall control of a ‘Board of Revenue’ at Calcutta, a weak system, rightly characterized by Hastings as “petty tyrants and heavy rulers of the people”. The foundation of the civil service in the modern sense was, nonetheless, laid down during his regime.

(a) Hastings, having proficiency in Bengali, Urdu, Persian, understood the relationship between on acculturated civil servant and an efficient one and accordingly emphasized on the creation of an ‘orientalized elite club of the civil servants’, competent in Indian languages and responsible to Indian tradition.

(b) He made efforts at lifting the moral tone and intellectual standards of servants. ‘Dastaks’ were abolished in 1773 and those engaged in the private trade had to pay a duty of 2½% to the Board of customs.

(c) Hastings separated the revenue and commercial branches as also revenue from the judicial functioning.

(d) The Regulation Act of 1773 prohibited all officials of the Company, from the Governor-General and his councilors and Chief Justice and other judges of the Supreme Courts downwards, from accepting gifts, donations, gratuity or rewards. If found guilty of doing so, they could be legally convicted by the Supreme Court or the court of the Mayor.

(e) In 1780-81, revenue and judicial administration in districts was entrusted to English officers which was the beginning of the ‘nucleus’ of the civil service with systematization and specialization of functions, essential to such service.

(f) By Pitt’s India Act of 1784, they were provided with definite scales of pay and emoluments.

Practices of Cornwallis:

Thus Hastings laid the foundation on which Cornwallis built a superstructure. Cornwallis, who came to India as Governor General in 1786, was determined to “purify” the administration.

(a) He enforced the rule against the private trade and acceptance of presents and brides by official with strictness.

(b) He raised the salaries of the civil servants with the fact in mind that the Company’s servants would not give honest and efficient service so long as they were not given adequate salaries. Collector of a district was, therefore, to be paid Rs. 1500/- a month and 1% commission on the revenue collection of his district. In fact, Company’s civil service now became the highest paid service in the world.

(c) Cornwallis also laid down that promotion in the civil service would be by seniority so that its members would remain independent of outside influence.

(d) A special feature of the Indian civil service since the days of Cornwallis was the rigid and complete exclusion of Indians from it. It was laid officially in 1793 that all higher posts in administration worth more than $500 a year in salary were to be held by Englishmen. This policy was also applied to other branches of administration and Government, such as they army, police, judiciary, engineering, etc.

(e) He reduced the number of collectors from 36 to 23.

(f) He organized the administration four divisions (i) Public or General, (ii) Revenue, (iii) Judicial and (iv) Commercial.

College of Fort William:

From the middle of the 18th century, Company’s territorial empire in India started expanding but the Company servants were not efficient and suitable to the requirement. It was under this backdrop that Wallesley established the College of Fort William at Calcutta in 1800, with an intention of having an “Oxford of the East” at their disposal. The directors of the Company, however, disapproved of his action and in 1806 and replaced it by their own East India College at Haileybury in England.

Charter Act, 1833:

One thing to be noted is that prior to 1833 Charter Act, there was no element of competition, whatsoever. The Court of Directors remained supreme in selection and appointment of civil servants, in the direction and supervision of East India College and, in fact, in any other matte concerned directly or indirectly with the exercise of patronage.

The change that followed the enactment of 1833 was mainly in two directions-First, the imperial control of Company’s civil service became direct exercisable immediately by the Board of Control, a parliamentary body. Secondly, the disciplinary control of the Government of India over civil servants became more pronounced than ever before.

Their appointment still continued to proceed from the Court but increasing directness of relationship between the Board of Control and the Government of India could not but relegate to the background both the influence and the authority of the Company exercised before.

The Charter Act of 1833 specifically provided that no Indian should be debarred from holding any office by reason only of his religion, place of birth, descent or colour. In other words, there should be “no governing caste” in British Indian and that capacity and not race as to be the criterion of eligibility for administrative service.

Indians were accordingly appointed in increasing numbers to responsible judicial and executive posts, but not to the corps de ‘elite’ represented by Indian civil service, which had a monopoly of the higher posts.

Charter Act 1853:

Provision for open competition was first made by the Charter Act of 1853. The old powers, rights, and privileges of Court of Directors to nominate candidates for admission to Haileybury were to cease in regard to all vacancies which occurred on or after April 30, 1854.

This Act provided that subject to such regulations as the Board of Control might make from time to time ‘any person being a natural born subject of Her Majesty’ who may be desirous of being admitted into the said college at Haileybury shall be admitted to be examined as a candidate for such admission.

(a) The appointment of civil servants was to proceed from the Court of Directors as before, but it could appoint only such person as were declared entitled under the regulation so framed by the Board of Control.

(b) A five member committee with T.B. Macaulary as Chairman was appointed to decide the preconditions and mode of examination.

(c) The maximum age for admission was at first 23 (the minimum being 18), in 1859 it was lowered to twenty two and selected candidates were to remain on probation in England for one year.

(d) In 1866, the maximum age was further lowered to 21 and the probationers had to go through a special course of training at an approved university for two years.

It was extremely difficult for Indians to pass this examination. The journey to England was not only expensive and unfamiliar but, in case of the Hindus, was frowned upon by the more orthodox leaders of the community.

To compete with the English boy since an examination conducted through the medium of English in an English University was indeed a formidable task. It was no wonder, therefore, that comparatively few Indians were successful.

Indians to the Higher Offices:

British Government realized the inadequacy of the Indian element in the superior civil service

(a) In 1870, an act was passed authorizing the appointment of Indians to the higher offices without any examination, but it came into effect only in 1879.

(b) The rules adopted in 1879 ordained “that a proportion not exceeding one sixth of the total number of covenanted civil servants appointed in any year by the Secretary of State should be natives selected in India by the local governments subject to the approval of the Governor-General-in- Council.”

These officers were called “statutory civil servants” and were recruited from “young men of good family and social position possessing of fair abilities and education”. The system was, however, subject to same defects from which all systems of nomination were bound to suffer.

Even Indians themselves preferred competitive examination. But in order to give Indians a fair and equitable chance, they recommended that there should be simultaneous examinations both in England and in India.

For the same reason they were against lowering of the maximum age of admission below 21 as it would adversely affect the Indian candidates who were to be examined in a foreign tongue. The lowering of the maximum age limit to nineteen in 1877 was regarded as a deliberate attempt to shut out Indians and led to an agitation which culminated in the Congress movement.

The Congress vigorously took up the question of simultaneous examination and employment of Indians in larger numbers.

Public Service Commission:

In 1886, Lord Dufferin appointed a “Public Service Commission” to investigate the problem with Sir Charles Atchnison as its president.

(a) The Commission rejected the idea of simultaneous examination for covenanted service, and advised the abolition of the statutory civil service.

(b) It proposed that a number of pasts, hitherto reserved to covenanted service should be thrown open to a local service to be called the Provincial Civil Service, which would be separately recruited in every province either by Promotion from lower ranks or by direct recruitment.

(c) The terms covenanted and un-covenanted were replaced by Imperial and Provincial, and below the latter would be Subordinate Civil Service. The recommendations were accepted. The covenanted civil service was hence forth service was called after the particular province, as for example, the Bengal Civil Service. A list of posts reserved for the Civil Service for India, but open to the new provincial service, was prepared and local governments were empowered to appoint an Indian to any such “listed post”.

In other branches of the administration such as Education, Police, Army, Public Works and Medical departments, too, there were similar divisions into imperial, provincial and subordinate service. The first was mainly filled by Englishmen, and other two almost exclusively by Indians.

Examination in India:

In 1893, the House of Commons passed a resolution in favour of simultaneous examinations in England and India for the Indian civil services. The resolution was forwarded S.O.S. to the Government of India which opposed the resolution and thus nothing came out of the proposal.

Commission on the Public Services in India:

During the early years of 20th century Indians continued to agitate for a greater share in the public services. In September 1912, a royal commission on the public services in India was appointed. With Lord Islington as chairman. It recommended:

(a) That besides the recruitment of Indians to the I.C.S. through the London examination, 25% of the posts in the Superior Civil Service should be filled from among Indians, partly by direct recruitment and part by a promotion from the lower service.

(b) To make the working of this scheme possible, it also recommended the holding of an examination in India for the recruitment of civilians, thus conceding to the Indians, in a changed from what they had been demanding for more than half a century.

Montagu-Chelmsfod Report:

The authors of the Montagu-Chelmsford Report took a more liberal sympathetic view than the Islington Commission on the question of Indian zing the civil services. They proposed that,

(a) 33% of the superior posts should be recruited in India, and that this percentage should be increased by 1 ½ % annually.

(b) All racial distinctions in the matter of appointment should be abolished.

(c) For all the public services for which there was a recruitment in England open to Europeans and Indians alike, there must be a system of appointment in India.

For about four years, the above principles were followed in the matter of recruiting Indians. Royal Commission

To solve certain difficulties continuing in the service, a Royal Commission was appointed in June, 1923, with Lord Lee of Fareham as Chairman. The Lee Commission submitted its report in 1924 and most of its recommendations were accepted by the Government.

(a) The Commission recommended that All India officers of the Indian Civil Service, the Indian Police Service, irrigation branch of the Service of Engineers and the Indian Forest Service should continue to be appointed by S.O.S.-in-Council, while the services of the transferred departments should be controlled by provincial governments, except the Indian Medical Service, for which each province was to appoint in its Civil Medical Department a certain number of officers lent by the Medical Department of army in India.

(b) As regards, Indianization of services which were still to be controlled by S.O.S., the Commission recommended that 20% of the officers should be recruited by promotion from provincial civil services, and of the remaining 80%, half should be British and half Indian. It calculated that by following the principle, there would be equal number of Europeans and Indians in Superior Civil Services in 1939.

(c) It recommended the immediate establishment of a Public Service commission. Such a Commission, composed of five whole time members, was appointed in 1925.

(d) After 1922, certain officers in the Indian civil services were recruited on the result of a competitive examination held in India.

Rights and Status of the Civil Servants:

Part X of the Government of India Act, 1935 defined the rights and status of the civil servants. It also provided for a Federal Public Service Commission and Provincial Public Service Commission’s; but two or more provinces might agree for one commission. The functions of commissions were purely advisory. They could only recommend names, which the ministers, atleast in some cases, might accept or reject.

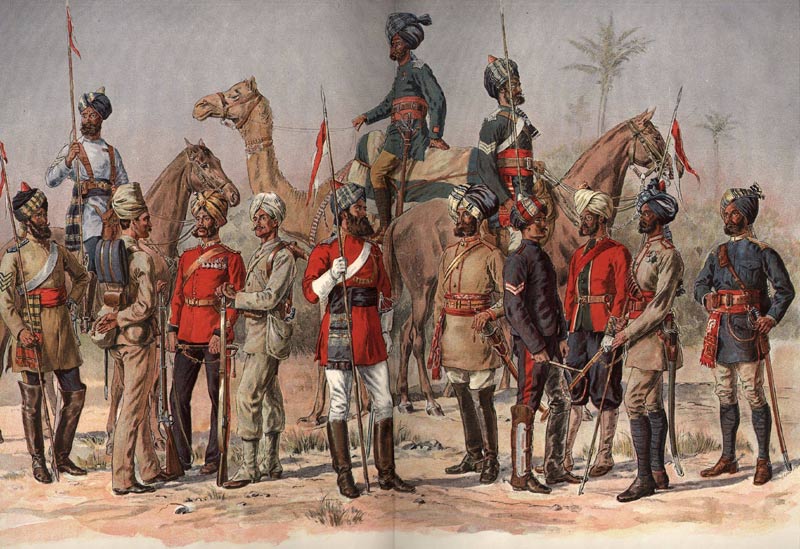

Army:

Before 1857 Revolt:

Although the Indian civil service is usually described as the ‘steel frame’ of British administration, the ultimate basis of the British rule in India had always been the Indian Army, that aptly be described as ‘the second important pillar of the regime.’ It fulfilled four major functions:

(a) It acted as the principal imperial tool through which the Indian powers were conquered.

(b) It defended British Empire in India from the rival imperial powers.

(c) If safeguarded the ‘British hegemony’ and therefore, an apt British answer of internal disturbances and revolt.

(d) It was the chief instrument in extending the British imperial from Indian to Asia and Africa.

II. Up to the Revolt, an even for a long time after that, the presidencies of Bengal, Bombay and Madras maintained separate armies under separate army commanders. Although the Commander- in-Chief of Bengal Army became nominally the head of the military forces in India, the Governments of Bombay and Madras managed their own forces.

III. But an act was passed in 1893 whereby the whole army of India was placed under the single control of the Commander-in-Chief and was divided into four territorial units-those of Bengal, Madras, Bombay and Punjab-each under Lieutenant-General.

IV. In 1904 Lord Kitchner made a new organization on different lines. The Indian military forces were organised into three army commands and nine divisions. The advantage of this system lay in the fact that it co-ordinated the organization in time of peace with what would be necessary in time of war.

V. Each Presidency-army originally consisted to three elements, viz., (1) Indian troops, mostly locally recruited, (2) European units belonging to the Company and (3) Royal regiments. After 1858, the last two had to be amalgamated, but this provoked great discontent amongst the Company’s troops and about 10,000 men claimed their discharge. This is known as ‘White Mutiny’. The discontent was, however, allayed by the offer of a bounty and other concessions.

After 1857 Revolt:

I. But the ‘1857 revolt’ forced the British Government to introduce changes in the structure of army. Several steps were taken to minimize, if not completely eliminate, the capacity of Indian soldiers to revolt.

(a) The domination of army by its European branch was carefully granted through raising the proportion of Europeans to Indians and was fixed at ‘one to two’ in the Bengal Army, and two to five in the Madras and Bombay armies.

(b) The European troops were kept in key geographical and military positions.

(c) The crucial branches of army like artillery and later in 20th century, tanks and armoured crops were put exclusively in European hands.

(d) The older policy of excluding Indians from the officers’ corps was strictly maintained. Till 1914 no Indian could rise higher than the rank of a subedar.

(e) The organization of the Indian section of the army was based on the policy of ‘balance and counter-poise’ or ‘divide and rule’ so as to prevent the chance of uniting against in an anti- British uprising.

(f) Discrimination on the basis of caste, region and religion was practised in recruitment to the any. A fiction was created that Indians consisted of ‘martial’ and ‘non-martial’ classes. Soldiers from Awadh, Bihar, Central India and South India, who had first helped the British to conquer India but later participated in the revolt, were declared to be non-martial.

They were not taken in the army on a large scale. On the other hand, Punjabis, Gorkhas, Pathans who had assisted in the suppression of the revolt were declared to be ‘martial’ and were recruited in large numbers. By 1875, half or the British army was recruited from Punjab.

(g) In addition, Indian regiment were made a mixture of various castes and groups which were so placed as to balance each other, Communal, caste, tribal and regional loyalties were encouraged among the soldiers so that the sentiment of nationalism would not grow among them.

(h) It was isolated from nationalist ideas by every possible means. Newspapers, journals and nationalist publications were prevented from reaching the soldiers.

II. There might have been some justification for the curious anomaly when each Presidency maintained a separate army, but when all the Indian forces were brought under the single control of Commander-in-Chief in 1895, the anomaly called for redress. (The anomaly being the representatives of the army in the Governor General’s executive council at the same time-the Military Member, started appointing from 1861, and the Commander-in-chief).

Lord Kitchner took up this question in 1904 and proposed to remove the anomaly by making the Commander-in-chief the sole advisor of the Government on military matters. Lord Curzon, the Viceroy, strongly opposed the proposal, as the feared that it would remove, to a large extent, the ultimate control of the civil over the military authorities and thereby, S.O.S., however, supported Kitchner and his decision was conveyed in such terms that Lord Curzon tendered his resignation in 1905.

III. The Command System introduced by Lord Kitchner in 1904 was abolished by him in 1907 when the Indian army was divided into two sections, the Northern and the Southern.

IV. The first World War (1914-18), during which Indian troops of all descriptions rendered valuable services, showed the defects of the system and it was thus re-organized after the war:

The Indian Territory was divided into four commands, subdivided into 14 districts, each district containing a certain number of brigade commands. One of these, the Western command was abolished in November, 1938.

V. The defence forces of India consisted in 1939 of the Regular army, including units from the British army; the Auxiliary force, the membership of which was limited to European, British subjects; the Territorial force, composed of three main categories, provincial battalions, urban units and the University Training Corps units; the Royal Air Force from 1932.

There was also the Indian State Forces, formerly known as the Imperial Service Troops, raised and maintained by the rulers of the states at their own: cost and for State Service. VI. There were two main categories of officers in Indian army, those holding King’s commission and those holding Viceroy’s commission.

The latter were all Indians having a limited status and power of command. As for the King’s commission, the Indians had been eligible for it since 1918 in three ways:

(a) By qualifying themselves as the cadets at the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, and the Indian Military Academy, Dehradun (opened in 1932).

(b) By selection, of efficient Indian officers or promotion of non-commissioned officers of the regiments.

(c) By award of honorary king’s commission, to officers who cannot quality themselves for these on account of their advanced age or lack of education.

With the progress of Nationalist Movement in India, her people demanded a definite control over the defence administration. Our Nationalist leaders continuously and insistently complained against the heavy expenditure which, according to them was a ‘dangerous’ national waste, if diverted constructively to the Indian interest, possessed potential of ‘national-building’.

The Montagu-Chelmsford Report, after praising the brilliant and faithful services of Indian Army in the World War I, emphasized “the necessity of grappling with the problem” of Indianizing it further. The Nehru Report advocated the transfer of control over the Indian Army to the ministers.

The Skeen Committee, appointed in the June, 1925, with Major-General Sir Andrew Skeen, as chairman and commonly known as the Indian Sandhurst Committee, recommended the abolition of “eight unit scheme” (announced by Lord Rawlinson in 1923) and the establishment of an Indian “Sandhurst” by 1933.

These recommendations were not fully carried out. Indian Security Commission considered the ‘cardinal problem’ of national defence in a totally different perspective, and insisted on the presence of British element in the Army on three considerations-frontier defence, internal security and obligations to the Indian States. No substantial change was made in the matter of India’ defence by the Government of India Act, 1935.

Police:

I. The third pillar of the British imperialism in India (the first and second being the civil service and army respectively) was the police.

II. It was through this instrument the Mai-Baap ‘myth’ of the British administrators was created which in a way helped the British Imperialism to build a ‘cultural hegemony’ over ever quarrelling masses of India, a mere geographical expression, they claimed and legitimized.

III. Though ‘a system of circles or thanas headed by daroga with its sepoys was rather a modern concept, evolved once again by Cornwallis, but a two-tier police administration with the Nazim or Governor at the provincial headquarters and the faujdar with a contingent of military police in the district, a primitive police system was present even in Mughal period.

The existence of a local subordinate functionary called Shigdar is referred to at places but he does not seem to form a part of the regular hierarchy of police officials. The other significant character to Mughal ‘proto-police system’, i.e. the existence of a ‘non-official peace-keeping force’, intended primarily for the land revenue collection but also invested with the responsibility of law and order, had its root in the village-system.

With the disintegration of central authority of the Mughals, the official and private instruments of the police began to work at cross-purposes, the latter becoming increasingly independent of the former especially in the districts under the Zamindar or revenue-farmers’ leadership.

IV. With the arrival of the British on the Indian political platform, the system of official and un-official police system, working for cross-purposes, needed a change for the obvious reasons. But the daroga system introduced by Cornwallis in 1792 did not remain limited to reducing the non-official apparatus to the ‘original intention’ of the instruction.

The private system was struck off. The Zamindars and farmers were altogether divested of their local responsibility and were asked to disband their militia.

(a) The police daroga of Cornwallis, who stepped into the position previously occupied by Zamindari thanedars, became a direct instrument of Government operating under the direct control of the English magistrate.

(b) The authority of daroga extended to the village watchmen and although their appointment and emolument remained for time being with the Zamindars, it was not long before they became stipendiary servants for the Government.

(c) The village Militia, which under the Mughals were paid and controlled by the community, became the stipendiary servants of government under British.

(d) The agency through which the change was brought about was that of the police daroga.

(e) In the big cities the old office of kotwal was, however, continued, and a daroga was appointed to each of the wards of a city.

V. Another important feature which distinguished the police reforms of British was the introduction of a coordinating agency under special and expert control exercisable over a group of magistrates by a separate civilian superintendent of police appointed in 1808 for the divisions of Calcutta, Dacca and Murshidabad and in 1810 for those of Patna, Benarasand Bareilly.

It was a controlling function which later came to be rested in the Divisional Commissioners appointed under Regulation I of 1829. Earlier under Mughals, there had been no such agency between the faujdar and Nazism.

VI. The search for a general system of police for the whole of British India proceeded in 1860fromtwo main considerations, efficiency and economy. A police force had been organized for Punjab in 1849 on the lines comparable to those of Sind.

It consisted of a military preventive police and a civil detective police. In ‘Mutiny’, this force contributed effectively to the restoration of order. But it involved serious financial burdens, and the financial crisis that followed the; Mutiny’ necessitated an immediate reduction of cost and therefore a commission was appointed. The Commission (1860) recommended.

(a) The abolition of the military police as a separate organization and the constitution of single homogeneous force of civil constabulary for the performance of all duties which could not properly be assigned to its militarily arm.

(b) The discipline and internal management of the force so established was to be vested in an Inspector General of Police.

(c) He was to be assisted by a District Superintendent in each district, with an Assistant Superintendent in case the size of a district happened to be unusually large, both these officers being European, and the I.G. being, on occasion, of the Indian Civil Service, and sometimes an officer of the police department created for each of the provinces.

(d) The subordinate force below them was to consist of inspector, head constables, sargents and constables; the head constable being in-charge of a police station, while the Inspector, of a group of such stations.

(e) The village police was to remain an official apparatus.

(f) It was specifically laid down that Divisional Commissioners should cease to be Superintendents of police.

(g) On the question of the relation between magistracy and the police the commission made it clear that no magistrate of rank lower than the District Magistrate should exercise any police function.

VII. The Commission submitted the draft of a Bill on the pattern of Madras Police Act (1853) to give effects to its recommendations, and this was passed into Act V of 1861. The importance of the traditional co-operation of the community was thus completely lost sight of, and responsibility for all police work was entrusted on regular police officers at subordinate levels who were for the most part untrained and ill-educated.

Once again, the Indians were excluded from all superior posts due to the very logic of imperialism. The police was, on the whole, unsympathetic to the native population which was obvious, for they were not meant for restoration of law and order to promote Indian interests, but they wanted to restore it to make it possible and possible for further unending process of ‘colonial’ exploitation and ‘drain of Indian wealth’ to the mother country, the shop-keepers of the world, the ‘Great Britain’.

Judiciary:

Earlier, the administration of justice used to be under the Zamindars and the process of dispensing justice was often arbitrary.

Reforms under Warren Hastings (1772-1785):

i. District Diwani Adalats were established in districts to try civil disputes. These adalats were placed under the collector and had Hindu law applicable for Hindus and the Muslim law for Muslims. The appeal from District Diwani Adalats lay to the Sadar Diwani Adalat which functioned under a president and two members of the Supreme Council.

ii. District Fauzdari Adalats were set up to try criminal disputes and were placed under an Indian officer assisted by qazis and muftis. These adalats also were under the general supervision of the collector. Muslim law was administered in Fauzdari Adalats.

The approval for capital punishment and for acquisition of property lay to the Sadar Nizamat Adalat at Murshidabad which was headed by a deputy nizam (an Indian Muslim) assisted by chief qazi and chief mufti.

iii. Under the Regulating Act of 1773, a Supreme Court was established at Calcutta which was competent to try all British subjects within Calcutta and the subordinate factories, including Indians and Europeans. It had original and appellate jurisdictions. Often, the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court clashed with that of other courts.

Reforms under Cornwallis (1786-1793):

i. The District Fauzdari Courts were abolished and, instead, circuit courts were established at Calcutta, Dacca, Murshidabad and Patna. These circuit courts had European judges and were to act as courts of appeal for both civil and criminal cases.

ii. The Sadar Nizamat Adalat was shifted to Calcutta and was put under the governor-general and members of the Supreme Council assisted by the chief qazi and the chief mufti.

iii. The District Diwani Adalat was now designated as the District, City or the Zilla Court and placed under a district judge. The collector was now responsible only for the revenue administration with no magisterial functions.

iv. A gradation of civil courts was established (for both Hindu and Muslim laws):

(i) Munsiffs Court under Indian officers,

(ii) Registrar’s Court under a European judge,

(iii) District Court under the district judge,

(iv) Four Circuit Courts as provincial courts of appeal,

(v) Sadar Diwani Adalat at Calcutta, and

(vi) King-in-Council for appeals of 5000 pounds and above.

The Cornwallis Code was laid out:

a. There was a separation of revenue and justice administration.

b. European subjects were also brought under jurisdiction.

c. Government subjects were answerable to the civil courts for actions done in their official capacity.

d. The principle of sovereignty of law was established.

Reforms under William Bentinck (1828-1833):

i. The four Circuit Courts were abolished and their functions transferred to collectors under the supervision of the commissioner of revenue and circuit.

ii. Sadar Diwani Adalat and a Sadar Nizamat Adalat were set up at Allahabad for the convenience of the people of Upper Provinces.

iii. Till now, Persian was the official language in courts. Now, the suitor had the option to use Persian or a vernacular language, while in the Supreme Court English language replaced Persian.

1833:

A law Commission was set up under Macaulay for codification of Indian laws. As a result, a Civil Procedure Code (1859), an Indian Penal Code (1860) and a Criminal Procedure Code (1861) were prepared.

1860:

It was provided that the Europeans can claim no special privileges except in criminal cases, and no judge of an Indian origin could try them.

1865:

The Supreme Court and the Sadar Adalats were merged into three High Courts at Calcutta, Bombay and Madras.

1935:

The Government of India Act provided for a Federal Court (set up in 1937) which could settle disputes between governments and could hear limited appeals from the High Courts.

Positive Aspects on Judiciary under the British:

i. The rule of law was established.

ii. The codified laws replaced the religious and personal laws of the rulers.

iii. Even European subjects were brought under the jurisdiction, although in criminal cases, they could be tried by European judges only.

iv. Government servants were made answerable to the civil courts.

The Negative Aspects:

i. The judicial system became more and more complicated and expensive. The rich could manipulate the system.

ii. There was ample scope for false evidence, deceit and chicanery.

iii. Dragged out litigation meant delayed justice.

iv. Courts became overburdened as litigation increased.

v. Often, the European judges were not familiar with the Indian usage and traditions.

Local Self-Government:

Presidency Towns:

The earliest efforts in Municipal administration in India were made in the Presidency Towns of Madras, Calcutta and Bombay. In 1687, an order of Court of Directors directed the formation of a Corporation of Europeans and Indian members of the city of Madras but the Corporation did not survive. Under the Regulating Act of 1773, the Governor-General nominated the servants of the Company and other British inhabitants to be the Justices of Peace.

They were empowered to appoint scavengers for the cleaning and repairing of the streets of Calcutta, Madras and Bombay, for making assessment for those purposes and for the grant of licences for the sale of spirituous liquors.

The reason for this provision was the insanitary state of affairs in the Presidency Towns. Between 1817 and 1830, spasmodic attempts were made in Madras and Calcutta to undertake works paid out of the lottery funds and much was done with this money in laying out those towns.

On completion, the roads and drains were handed over to the Justices of Peace to be maintained by them out of their assessments. However, even for maintenance work, the funds never sufficed. In Bombay, a tax on carriages and carts was levied for the purpose of making roads. In 1840, an Act was passed for Calcutta and in 1841 for Madras.

Those Acts widened the purposes for which the Municipal assessment was to be utilized. The inhabitants of the town were given control over the assessment and collection of taxes. However, much did not come out of those Acts.

There was no response from the public. In 1845 an Act was passed for Bombay. It concentrated the administrative powers in the hands of a Conservancy Board on which were two Europeans and three Indian Justice, with the senior Magistrate of Police as Chairman.

A fresh attempt to deal with the sanitation of the Presidency Towns was made in 1856. One Act dealt with the conservancy and improvement of the Presidency Towns. The second Act provided for the assessment and collection of rates.

Special Acts were passed for the appointment of three Commissioners in each town. Special provision was made for gas lighting and construction of sewers in Calcutta. Bombay Act of 1858 gave power to levy dues. In spite of this legislation sanitary conditions remained most unsatisfactory.

Outside the Presidency Towns:

Outside the Presidency Towns, there was practically no attempt at Municipal legislation before 1842. An Act was passed in that year in Bengal but it remained a dead letter. An Act of 1850 was made applicable to the whole of British India. The Act was of a permissive nature.

The Government of any province was given the power to bring the Act into operation ‘n any town if it was satisfied that the inhabitants of the town wanted it. A large number of municipalities were set up in all provinces. In most provinces, the Commissioners were nominated by Government.

Mayo’s Resolution of 1870:

It was only after 1870 that real progress was made in the direction of Local Self-Government. The Resolution of 1870 dealing with Decentralisation of finance referred to the necessity of taking further steps to bring local interest and supervision to bear on the management of funds devoted to education, sanitation, public works etc. Between 1871 and 1874, new Municipal Acts were passed in various provinces and they extended the elective principle.

Ripon’s Resolution of 1881:

The next step was taken by Lord Ripon who has rightly been called the Father of Local Self- Government in India. His resolution on Local Self-Government is a great landmark in the growth of local self-government in the country.

It was stated in the Resolution of 1881 that the Governor-General of India was of the view that time had come when further steps should be taken to develop the idea of Lord Mayo’s Government. It was asserted that agreements with the Provincial Governments regarding finance should not ignore the question of Local Self-Government.

The Provincial Governments were directed to transfer considerable revenues to the local bodies. The Government of India directed the Provincial Governments to undertake a careful survey of the provincial, local and municipal Acts.

The object of the inquiry was to find out what source of revenue could be transferred from the provincial to the local heads so that they could be administered by the Municipal Committees. It was also to be administered by the Municipal Committees. It was also to be investigated what items could safely be given to the local bodies.

Only those items were to be transferred which were understood and appreciated by the people. Another object of the inquiry was to devise steps which were “necessary to ensure more Local Self-Government”. Letters were sent to the Provincial Governments.

The Government of India hinted at those items of expenditure that could conveniently be transferred to the local bodies for control. The Provincial Governments were directed to examine other items also which could be handed over to the local bodies. The Government of India recommended that the District Magistrate or the Collector should be the President of the District Committees and Assistant or Deputy Commissioner the President of subordinate committees.

In those committees, the number of the non-official members was to be not less than one-half and not more than two-thirds of the whole. The Provincial Governments were told that “it would be hopeless to expect any real development of Self-Government if the local bodies were subject to check or interference in matters of detail”.

The Governor-General was serious that fullest possible liberty of action should be given to the local bodies. The Provincial Governments not only approved of the policy contained in the resolution of 1881 but also submitted their schemes to the Governments of India.

Resolution of 1882:

Another resolution was passed in 1882. Lord Ripon took special pains to make it clear that the expansion of the system of local self-government would not bring about a change for the better from the point of view of efficiency in municipal administration.

Lord Ripon indicated the general lines on which further steps were to be taken so that some real and substantial progress might be made in the field of Local Self-Government. The first part of the recommendations was concerned with the fundamental principles. Local Governments were directed to maintain and extend a network of Local Boards in every District.

The area and jurisdiction of every Local Board was to be so small that local knowledge and local interest on the part of the members of the Board could be secured. The number of non-official members was to be very large and the official element was not to exceed one-third of the whole.

However, the second part of the recommendations of the Government of India was concerned with the degree of control to be retained by the Government over the Local Boards. The Government control should be exercised in two ways.

In the first place, the sanction of the Government should be made necessary to legalise certain actions of the Local Boards, e.g., raising or levying of taxes, etc. The number of cases where sanction was required was to be large at the beginning but was to be reduced later on as the Local Boards got more experience. Secondly, the Local Government was authorised to interfere either to set aside altogether the proceedings of the Board in particular cases or to suspend them temporarily in cases of crises and continued neglect of their duty.

The power of absolute supersession was to be exercised only with the consent of the Government of India. The Local Government were directed to hand over to the Local Boards complete control over the local rate and cesses, licences, tax assessments and collections, pounds and ferry receipts etc. The Local Boards were to be granted lump-sum grants from the provincial revenues.

The District Engineer was to help the local bodies in their work of supervision and maintenance of buildings, but he was to work as their servant and not as their master. The Local Boards were to be left free in the matter of initiative and direction of operations.

Whatever be the importance of Ripon’s Resolution, it cannot be denied that both the Provincial Governments and the Governments of India did not carry out the policy laid down in the Resolution.

The result was that even after the lapse of 36 years, when another Resolution was passed in 1918, no substantial progress had been made in the field of local self-government. The British bureaucracy in India was determined to see that local bodies did not succeed in their work. The result was that all the wishes and good-will of Lord Ripon could not and did not improve the state of affairs in the country.

Decentralisation Commission Report (1909):

The Royal Commission on Decentralisation examined the whole question of Local Self-Government in India and made important recommendations. Particular reference was made to the lack of financial resources and their adverse effect on the working of local bodies. The Commission put emphasis on the importance of village Panchyats and recommended

1. The adoption of special for their revival and growth.

2. Village Panchayats should be given powers like summary jurisdiction in petty civil and criminal cases, incurring of expenditure on village scavenging the minor village works, the construction, maintenance and management of village schools, the management of small fuel and fodder reserves, etc.

3. Village Panchayats should be given adequate sources of income and interference by District Officers should be circumscribed.

4. The establishment of a Sub-District Board in every Taluka or Tehsil. The sub-District Boards were not to be completely under the control of a District Board for the whole district. Separate duties and separate sources of income were to be given to Sub-District Boards ad District Boards.

5. About the municipalities the withdrawal of existing restrictions on their powers of taxation. The municipalities were to take primary education. Middle vernacular schools were also to be put under their control it they so desired. Municipalities were to be relieved of expenditure on secondary education, hospitals, famine relief, police, veterinary works, etc.

Resolution of 1918:

In 1918, the Government of India passed an important Resolution on Local Self-Government. The basic principle of that Resolution was that “responsible institutions will not be stably rooted until they are board-based and that the best school of political education is the intelligent exercise of the vote and the efficient use of administrative power in the field of Local Self-Government.

The general policy should be one of gradually removing all the unnecessary controls from the local bodies. The Government was to separate the spheres of action appropriate for local institutions from those appropriate for the Government. The Resolution formulated certain principles calculated to establish wherever possible complete popular control over local bodies.

It suggested an elected majority in all the Local Boards and the replacement of official chairman by the elected non-official chairman in the municipalities. The same was to be done in the case of rural bodies, wherever possible.

The minorities were to be represented by nomination. The franchise was lowered to such an extent that the constituencies became really the representatives of the tax-payers. This Resolution also put emphasis on the advisability of developing the corporate life of the village. The Government was to encourage the growth of village Panchayats. The only immediate Action taken on this Resolution was that the District Officer was relieved of his duty as the Chairman of the District Board in all the provinces except the Punjab.

The Report on the Indian Constitutional Reforms of 1918 examined the existing system of local Government in the country and came to the conclusion that throughout the educative principal had been subordinated to the desire for immediate results. As far as possible, there should be complete popular control in local bodies and highest possible independence from outside.

Under Dyarchy:

Dyarchy was introduced in the provinces by the Government of India Act, 1919 and under that Act the Department of Local Self-Government was transferred into the hands of an Indian minister who was responsible to the Provincial Legislature for the same. The result was that some good work was done during the period of dyarchy.

Laws were passed practically in all provinces to make local bodies as effective training grounds for higher responsibilities in the future. Practically all the Acts passed on Local Self-Government aimed at lowering the franchise, increasing the elected element to the extent of making it the immediate arbiter of policy in local affairs. Laws were passed in every province for the growth of village Panchayats.

The Simon Commission Report:

The Simon Commission Report contained certain references to Local Self-Government. It was pointed out that village Panchayats had not made much progress except in certain provinces.

The Commission recommended the increase of the control of the Provincial Government over local bodies so that more efficiency could be secured. The Commission also referred to the unwillingness of the elected members to impose new taxes.

Under Provincial Autonomy:

Provincial autonomy was introduced under the Government of India Act 1935. The Department of Local Self-Government came under the control of a popular minister who could afford to put more money at the disposal of the local bodies. Laws were passed practically in every province to give more functions to local bodies.

However, the sources of income of local bodies, instead of increasing, became less. Restrictions were imposed on the powers of the local bodies to levy or enhance terminal taxes on trades, callings and professions and municipal property. The result was that not much progress was made in the field of Local Self-Government.

Under Independent India:

India became independent in 1947. Article 40 of the Constitution provides that village Panchayats should be re-organised and more powers should be given to them so that they can function successfully. As units of Local Self-Government. Panchayati Raj Acts have been passed in many states with a view to give more powers to village Panchayats.

The Local Finance Inquiry Committee submitted its report in 1951. It referred to the hopeless financial condition of local bodies and made recommendations to improve the same.

The view of the Committee was that “with the grant of larger powers will come an increased realisation of responsibility and the growth of improved public opinion will constitute a check which will prove more effective than financial intervention.”

Defects in the Present System:

Local bodies have to face many handicaps. There is an all embracing control of the executive in every field of activity. This undoubtedly destroys all initiative on the part of the members of local bodies. Without initiative on the part of the people we can never hope to put vigour into the lifeless bodies of local institutions.

There is also the handicap of finance. Local bodies do not have enough of resources to perform their duties in such a way that they can add to the fullness and richness of lives of the people. New sources of revenue have to be found and the Government has to follow a liberal policy in the matter of grants-in-aid and the borrowing powers of local bodies. There is also the lack of public interest in the work of local bodies. There is also the lack of public interest in the work of local bodies.

All means of modern propaganda must be employed to emphasize on the people the importance of local bodies in the national life of the country and thereby induce them to take interest in them. There is a dearth of books on the subject.

The result is complete ignorance on the part of the people with regard to local affairs. It is the greatest necessity of all concerned to take interest in local affairs. We should never forget that without a vigorous system of Local Self-Government in the country, the foundations of democracy will always remain weak and shaky.

Constitutional Changes (1909-1935):

The Indian Councils Act, 1909 or the Minto-Morley Reforms:

i. The size of the Legislatures, both at the Centre and in the Provinces, was enlarged and so were their functions.

ii. The Central Legislature was to consist of 69 members of whom 37 were to be officials while the remaining 32 non-officials (5 to be nominated by the Governor-General while the remaining 27 were to be elected). Thus an element of direct election to the Legislative Councils was introduced and officials majority in the central legislature was retained.

iii. The Act provided for non-official majorities in the provinces.

iv. Now the members of the legislatures at both the levels were’ given the right of discussion and asking supplementary questions. Detailed rules were laid down concerning the discussion of budgets in the Central Legislature but members were not empowered to vote.

v. The Act also introduced separate electorates for Muslims.

The Government of India Act, 1919:

1. The Secretary of state for India who used to be paid out of the Indian revenues was now to be paid by the British Exchequer. Some of his functions were taken away from him and given to the High Commissioner for India who was to be appointed and paid by the Government of India.

2. The number of Indians in the Governor-General’s Executive Council was raised to three in a Council of eight. The new scheme of Government envisaged a division of subjects into the Central List, which were to be administered by the Governor-General-in-Council, and the Provincial List.

3. The Act set up a bicameral legislature at the Centre in place of the Imperial Council consisting of one House. The two Houses were to be the Council of States (elected majority) and the Central Legislative Assembly (it was to consist of 145 members of whom 41 were to be nominated and 104 elected). The life of the Assembly was to be three years but it could be extended by the Governor-General.

4. The most significant changes made by this Act were in the field of provincial administration as it introduced Dynarchy in the provinces. Under this system, the subjects to be dealt with by the provincial Government were divided into two parts. Reserved and transferred subjects. The Reserved subjects were administered by the Governor with the help of the members of the Executive Council who were nominated by him and who were not be responsible to the legislature while the Transferred subjects were administered by the Governor acting with the ministers appointed by him from among the elected members of the Legislature and who were to be responsible to the Legislature and were to hold office during his pleasure.

The Government of India Act, 1935:

1. The Act provided for the establishment of an All-India Federation in which Governor’s provinces and the Chief Commissioners Provinces and those Indian States which might accede to the united, were to be included, (it did not come into existence since the Princely States did not give their consent for the union).

2. Dyarchy was provided in the Federal Executive. Defence, External Affairs, Ecclesiastical Affairs and the Administration of Tribal Areas were reserved in the hands of the Governor-General to be administered by him with the assistance of a maximum of three Councillors to be appointed by him. The other federal subjects would be administered by the Governor-General with the assistance and advice of a Council of Ministers to be chosen by him responsible to the Federal legislature.

3. The Federal Legislature was to have two chambers; the Council of State (members elected directly by the people) which was to be a permanent body with one-third of its membership being vacated and renewed triennially and the Federal Assembly (members elected indirectly by the members of the Provincial Legislative Assemblies on the basis of proportional representation with the single transferable vote) whose duration was fixed for five years. As regards the subject-matter of Federal and Provincial laws, there were three lists – the Federal legislative List, the Provincial Legislative List and the Concurrent Legislative List. Residuary legislative powers were vested in the Governor-General.

4. Another significant feature of this Act was the provision of responsible Government both at the Centre and the Province levels with safeguards.

5. Provincial autonomy was introduced and dyarchy in the provinces was abolished. Provincial legislatures were made bicameral, for the first time in 6 provinces (Bengal, Madras, Bombay, U.P., Bihar and Assam).

6. The separatist system of representation by religious communities (General, Muslim, European, Anglo-Indian, Indian Christian and Sikh) and other groups (Labour, Landholders, Commerce and Industry, etc.)

7. The Act provided for a Federal Court, with original and appellate powers. Federal Court at Delhi was established in 1937 with a Chief Justice.